When he heard news of the three missing young men, Haydn Willans, the manager of Muchenje Campsite, was in Ireland. He took immediate action and briefed the Kasane WhatsApp group in Botswana in the following post on 8 April 2024 at 12.23pm.

Good morning,

Help is urgently needed. 3 guests travelling under

the name of Drew in a Bushlore Hilux twin cab

registration KC 79 NY GP are missing. Last seen

leaving Muchenje Campsite and Cottages on 01

April 2024. Their next destination was supposed

to be Savuti Campsite on 01 April 2024, but no

record of entry at Goha gate and any movements

thereafter.

If anybody has seen or has any information regarding

this group please contact Andy from Drive Botswana

or myself – Haydn (Muchenje Campsite).

Thank you.

When I read this, as a seasoned safari guide myself, I didn’t think that much of it. They could have made any number of choices and be virtually anywhere. I knew that Bushlore vehicles are fitted with trackers so I sent a message to the owners and asked if we could get a GPS location. We could not because they had gone out of mobile signal range into the bush, but we did at least know which direction they had taken.

* * *

Charlie, Ted and Jack, all Londoners and lifelong friends, decided that the best form of stag party for Charlie’s upcoming wedding in December would be an unforgettable safari through Botswana’s National Parks. It certainly proved to be unforgettable.

They hired a 4×4 vehicle that was fully rigged out for camping and planned their itinerary in conjunction with their Botswana booking agent. It involved a mixture of camping and lodging and included a variety of activities. They stocked up with food for the expedition as well as an impressive stack of beer.

On the night of the 31st March 2024 they camped at Muchenje Campsite and the next morning – appropriately April Fool’s day? – they headed towards Savuti but instead of following the agent’s explicit, written directions they decided to take another route, which on the map was presented as a road on par with the main one to which they’d been directed but was the very road that John and Lorraine Bullen (see the preceding blog Death in the Endless Mopane) had followed on their fateful journey.

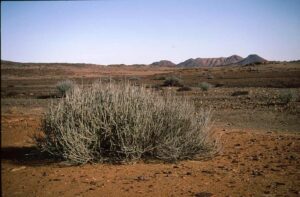

The young Brits’ journey through uncharacteristically dry country for early April was initially uneventful. El Nino had warmed the Pacific Ocean on the other side of the globe, which resulted in the seasonal rains not reaching Botswana from the north and were the lowest recorded in forty years. They followed the Chobe National Park boundary as it went south and then west until it turned sharply and headed north. If they had continued on the cutline they would have arrived at Goha Gate and comfortably been in their Savuti campsite by mid-afternoon but, instead, they chose to turn south towards the Ngwezumba River and take the track that follows the river in its journey towards the Savuti Marsh. They soon found that this is a road seldom travelled and at one point they lost the track entirely, but thanks to their GPS soon regained it. The last time I drove that road I found myself on an elephant path and had to bush bash my way back to the track, suffering punctured tyres in the process. Fortunately, I was travelling with friends in a convoy of three vehicles so there was no real danger.

The route was so seldom driven that the undergrowth in places blocked the view of the road ahead so the guys made slow progress, but that proved to be the least of their problems. The young mopane bushes, that were reclaiming the track, managed to snag and break their vehicle’s fuel line that connected its two fuel tanks. It did not take long to empty both tanks, leaving them stranded just short of a waterhole that held a small amount of muddy water. They pushed the vehicle into an open space overlooking the waterhole and planned their next move.

* * *

When I saw the digital map that showed the last place that they had been recorded I recognised instantly which road they had taken. It was the eastern cutline which can lead you to Nogatsaa or Zwei Zwei or Goha Gate depending on which turnoff you choose. I spoke to Andy, their agent from Drive Botswana and Rob from Bushlore and then Andrew from Helicopter Horizons. A flurry of phone calls saw me drive, with Steven from Bushlore in Kasane, some 70 kilometres through the Chobe National Park to meet up with a helicopter that had been sent from a lodge in Linyanti. We had prearranged to meet at a quarry near Ngoma Gate which was close to the start of the route that the youngsters had taken. Matt, a phlegmatic pilot from America, made it clear that I was in charge and that he would fly wherever I directed him. We took off following the cutline less than four hours after the alarm had been sounded, which bears testament to the clear prioritisation that everyone involved had lent to this search operation.

My hastily conceived plan was to follow the cutline and then the road that led to the Ngwezumba River. We could see that there were reasonably fresh tracks along the cutline which was encouraging but as it was eight days since the youngsters went missing, this was no positive confirmation that they had passed this way. When the cutline turned north towards Goha Gate we followed a lesser used road south towards the river. As we approached the river the waterholes were surprisingly full. It was clear that a powerful thunderstorm had hit the area. I couldn’t see any tyre tracks from the air and needed to do some scouting on foot to see if I could detect any sign of a vehicle having travelled along the Zwei Zwei road eight days earlier, so we set down near the junction, disturbing a small elephant herd who were drinking nearby and, much more alarmingly, a dagga boy, a lone, old buffalo bull widely regarded as the most dangerous animal in the bush. He bolted as we landed and when I followed the washed-out road on foot for about a kilometre I had no idea how far he had gone or how much our landing had disturbed him. There came a point where it was clear I would not find any sign of tyre tracks and I was feeling extremely vulnerable being out there alone, so I made my way back cautiously to the helicopter. We took to the air again and, as we were running out of light and fuel, we headed up the Ngwezumba river to Nogatsaa and then back to Ngoma. We had eliminated a lot of country, so we knew where they weren’t. The search would resume early the next morning. With time to prepare we would have more time and, critically, more fuel.

That night was a long one, spent co-ordinating the search that would unfold at daybreak the following day. The Botswana Defence Force and Police offered to do a ground search and I needed to ensure that we covered all possible roads. I organised flight times and arranged for a second helicopter from Maun, also courtesy of Andrew from Helicopter Horizons. Mike from Mack Air diverted his planes flying between Maun and Kasane to help cover the search area and offered to take me up in the afternoon if our early search had proved futile. Trish Williams, owner of Muchenje Campsite, arranged through Dr Kathy Alexander the Police and BDF involvement. So many people unhesitatingly did whatever they could. Trish also contacted Jason Drew, Charlie’s father, who lives in Cape Town. He was on the next flight to Johannesburg and was due in Kasane on the first flight the following day. We chatted when he landed in Johannesburg and I was relieved to hear his rather calm assuredness that these lads were level headed and reasonably bush wise. Nevertheless they had been stranded in the wild for nine days.

When the phones quietened, I pored over my collection of maps as well as Google Earth looking for likely places where they may have strayed from the track and where they might have landed up. I had two worries. The first was that they had lost the track and had driven through the bush until they had punctured tyres and could not move. That would expand the search area hugely. The second was if we found the vehicle deserted because they had decided to walk. Looking for three figures in that endless mopane would have been extremely challenging.

I went to bed around 1.30am with the alarm set for 4.30am. Steven was picking me up at 5.30am.

Matt was an hour later than the time I was given. It was not because of any tardiness on his part. He took off at sunrise which is the earliest time that he is allowed to take to the air but needed to refuel at another lodge which delayed him. As a result, we had less air time than I had expected so the plan was changed. We followed and eliminated a possible, if unlikely, road that headed towards Goha Hills and then followed the final section of the cutline that we had not covered the previous afternoon, arriving at the spot where we had set down on the first afternoon. We followed the indistinct track that John Bullen had taken and, at one point, even with the advantage of the aerial view, we had to double back to locate the road again. We were over my prime search area but there was no sign of them having passed, largely due to the heavy rains of a few days earlier.

We flew over the area where John Bullen’s vehicle had become stuck in the riverbed and years before that I, too, had been mired. As this was the same area where I had lost the road the last time I had taken it, I asked Matt to circle at a higher level to enable us to look out for a stranded vehicle, but we saw nothing so dropped back to our search altitude and continued over a section of the road that was in more open country. It was very familiar country to me and I reflected on how fortunate these guys were that I was looking for them here, because I doubt that anyone else knows it more intimately than I do. Nevertheless I had no idea where they were.

Matt is a superb pilot. He flew at just the right height and speed for us not to miss something below but also unhesitatingly responded to all my requests that we take a second look at a track from tree top level or double back because I wanted to check something out that I thought might be promising.

We flew over a pan where I used to regularly camp, and which some guests called Peter’s Pan (not to be confused with the pan in Savuti named after Peter O’Toole) and soon approached the area where I was camped when John Bullen had started his fateful walk.

Matt was following the track very considerately on the right-hand side so that I could watch for signs. I was starting to doubt that they could have made it this far and then got lost as the road was far more distinct than it was behind us and I was mentally planning on expanding the search into the limitless mopane. It was then that I saw what looked like a very organised campsite set up. Forgetting that I had headphones I tapped him urgently on the leg and indicated that he should circle back.

When he spotted them, he exclaimed with more feeling than I had expected from this calm pilot, “Yes! We’ve got them!”

Until that moment from the start of the search I had felt no emotion. It was a challenge that I had set for myself but when Matt uttered those few words I felt a brief flood of relief, but then stopped. What if it wasn’t them but some campers from Savuti? Or they had decided to walk through the bush? These thoughts stayed with me when we landed. I could see no sign of life. Then a person appeared from behind the vehicle and then two more. They were alive and we had found them.

As I alighted from the helicopter, a tall young man with tears streaming down his cheeks, arms outstretched, ran the hundred metres or so over an uneven pan to give me the most grateful hug of my life. Ted and Jack were slightly more reserved but no less relieved at their rescue.

There is no surprise there. These three city boys were stranded in deep African wilderness with limited stocks, herds of elephants coming to drink and with one bull seriously challenging them, questioning their presence in an area devoid of human activity. Their stories bubbled over, each experience told and retold. They had a 5l bottle of boiled beer which they offered to me to try. One sip was enough for me to know with absolute certainty that I would never walk into a restaurant and ask them to boil a beer for me, so I settled for a celebratory warm beer while we waited for the second helicopter to help with the evacuation.

They had survived. Nothing else matters. It must have been trying in the extreme enduring one interminably long, draining day after another, trying to plot their survival while hoping, expecting every minute of every day that someone would find them. They were ‘no shows’ in seven different lodges and activities. Surely one of the lodges or one of the operators that they had booked with would let their agent know that they had not arrived. Day after day they would desperately search the skies in vain for a rescuer while checking and re-checking their water and food supplies, boiling beer to retain its nutrients but get rid of the de-hydrating alcohol, collecting large piles of firewood to make smoke, burning their spare tyre, setting out aluminium foil in a cross in an open area to glint into the sky , making noise to fend off elephants. Catching rainwater when a large unseasonal deluge struck. Searching the skies for rescue. Praying that someone else would take the same road. And as the sun set night after night disappointment set in. Sleep would have been difficult. Lighting three fires around the vehicle to keep animals at bay.

They would have had endless discussions on the way forward. Do they walk? How far is it? If they decide to walk when would they leave? Could they get to Savuti in a day? If not, how would they spend the night without tents? Would they take the direct route which was a lot shorter than following the road? Planning over and over how many days’ food they had left before they would need to make the decision to walk. The batteries were starting to drain. Would they have enough for the GPS? Their thoughts would have tumbled over. Intense discussions the order of every day. One more glance to the skies… The mental strain would have been enormous.

Their final hope was that Bushlore would raise the alarm when their vehicle was not returned on time and they were not on the plane heading for Johannesburg – which is exactly what led to Haydn’s urgent message.

What did they do right? What mistakes did they make? We will discuss the narrow line between life and death in an upcoming blog.

Great read