One of the scariest experiences a person can have is to realise that they are utterly lost in the wilderness with no clue which way to go. I know. I have been there. It must surely rank alongside the helplessness of being diagnosed with a terminal disease or, perhaps, realising too late to do anything about it, that you doomed to spend the rest of your life as a politician.

Out there, the feeling of sheer vulnerability is acute, when frantically staring about you and seeing no landmarks whatsoever that will provide you with a hint of which way to go. Panic floods over you. That you can’t avoid – but you need a calm head, so you try to suppress your extreme anxiety. How well you achieve this could well determine whether you live or die.

What is the first lesson when you get lost in the wilderness? Anyone who has read the preceding four blogs (and if you haven’t, I urge you to do so now before continuing) should be screaming, “Don’t leave the vehicle!”

With that as the immutable law of survival, let’s look at each of the incidents in turn.

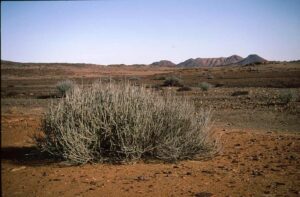

The Baron was outrageously arrogant and only survived due to having friends in high places. In Namibia, when they broke down at the site of the large welwitschia, he should have stayed where he was and allowed the guide to do his job. If he thought he would be able to help the guide he should have dressed appropriately, wearing a shirt, walking shoes and a hat, smeared himself in sunblock and taken plenty of water and food with him. He should then have looked back frequently to establish in his mind what a return journey would look like. Once he had set off with the guide he clearly should have stayed with him, no matter the circumstances. The guide here was far from faultless in not firmly telling his large guest what he should do.

When the Baron realised that he was lost, he should have quelled his rising panic, found a shady spot – if possible in that flat terrain – and waited for the heat of day to pass. He was already sunburnt and thirsty, so to continue to wander aimlessly in the scorching sun was a recipe for his own demise. Once he had calmed his mind, he would have realised that he would need to select a direction to take and then stick to it. People tend to walk in a large circle because their dominant side will cause them to sub-consciously favour that side. Many people, after hours of walking, are shocked to come across their own tracks when they believed that they were walking in a straight line. In the Baron’s case he must have been aware that the Atlantic Ocean, with its coastal road, lay to the west and he also may have been aware that the main road to Swakopmund lay to the north. On the way to view the welwitschia they had crossed the Swakop riverbed to the south, so he could have set off in any of these three directions to find safety, so long as he kept to one of them. I can hear you shouting at me that he didn’t have a compass on him and the GPS system was yet to be invented, so how could he possibly tell east from west, or north from south when lost on that featureless plain? Let us ignore the fact that the sun sets in the west so it is clear from late afternoon where the ocean lies and consider that you can tell direction at any time just by using a stick, or if you can’t find one, a stone or, in fact, anything that will stay still and cast a shadow. Push your stick into the sand, mark where the shadow is and wait for half an hour. The shadow will have moved so make a new mark. Join the two lines and you have your west to east line (because the sun rotates west to east as seen from the north pole). From there you can work out north and south and anywhere in between. Decide on the direction that you want to take and pick three objects in the distance that line up. Keep them in line as you walk, until you reach the first of them. Then find another one and line up again. In this way you will maintain your selected direction. You can double check by using your stick trick at any time that the sun is shining.

The Baron clearly should not have drunk the sap from that poisonous euphorbia. If you are unsure whether something is toxic, test it first on a sensitive part of your skin like the underside of your arms. If you don’t have a reaction, wipe a small amount on your lips and if you still don’t react, put a little inside your mouth. If there is still no sign of discomfort, swallow a small taste and wait for half an hour or so. If you still have no negative effects, you can assume that it’s probably safe to drink or eat. This in my view works for most foodstuffs except for celery which, in my considered opinion should be outlawed as a noxious weed, unfit for consumption. I will concede that perhaps when it comes to celery, I am moderately biased.

The young couple in the Okavango Delta should never have wandered far from the security of their guide and his mokoro. At the very least they should have frequently checked what the lie of the land looked like over their shoulder so that they would have had familiar landmarks to follow on their way back. To be fair, once you are lost in that part of the Okavango, everything looks much the same in every direction. Grass plains bordered by riverine trees tend to be indistinguishable and as there is no ocean, mountain range or highway to head for, settling on any one direction is somewhat arbitrary unless you are familiar with the area. Nevertheless, if you choose to walk rather than waiting for rescue, it remains crucial that you choose a direction and stick to it; you will come out somewhere, sometime if you travel in a straight line, rather than walking in a large circle if you don’t have purpose.

The burning of her clothes was a mistake that could have had fatal consequences. The girl then had no protection from the sun or the cold at night and the amount of smoke generated from those summer clothes would have been paltry and not attracted the attention of any pilot. She may have been better off waving them at a passing plane.

Once they realised they were lost and not likely to find their poler, the pair should also have realised that he would return to camp and raise the alarm and their best chance of survival would be to stay as close as they could to where they had left the mokoro, because a search for them would be launched first thing the next day. They should have found a shady tree, built a predator-resistant barrier of thorns and bushes and collected firewood for a large fire for the next day and made another to snuggle around overnight, keeping as warm as possible. The rescue plan would, most likely, involve an aerial search as well as a ground party. From early morning they should have lit a fire and gathered as many green branches and leaves as possible to throw on the flames to make them smoke. It would be seen from the air and the ground party would know where to look for them.

John Bullen, on the other hand, had no realistic expectation of a search party. No one knew that they were there, so no one would come looking for them – at least for weeks or maybe months. He chose to leave the vehicle, which proved to be a fatal mistake, but I understand why he did. At least he went prepared with suitable clothing, water, food and a GPS. What went wrong will forever remain a matter for speculation, but certainly his advanced age did not count in his favour.

The three youngsters from London, if they made a mistake, erred in choosing to take an alternative route to that described in detail by their agent and when they turned onto a track that clearly was seldom travelled, they had the option to turn around and take the far more frequented road to the Park gate. However, once they had broken down, they did everything well. Hoping that at some point a rescue party would be launched, they elected to stay with the vehicle and set about preparing themselves for their ordeal. They pushed the vehicle to a more visible spot, which proved crucial; they used foil and the emergency triangles to attract attention; they burnt their spare tyre as a smoke signal; they boiled beer to retain the nutrients without the dehydrating effects of the alcohol and they carefully rationed their food. When an unexpected thunderstorm struck, they spread out the protective roof-top tent canvas which collected enough water to fill the water tank and all their bottles.

If you are planning a trip on the wild side where there is any possibility of getting stranded in the wilderness – wherever you are – use modern technology. A GPS and a mobile phone are standard these days, but also consider a mobile Starlink system. You can email or What’s App anywhere in the world – ‘Hi Joe, you will never guess where I am,’ and then watch Survivor and Naked and Afraid on Netflix while you wait to be rescued.