Bees should terrify me. I am one sting from death, my doctor has told me. That was after one stung me deep in my throat when I took a swig of beer from a can we had unknowingly shared. Had my throat swelled then, as it might now, that may have been my last sip of beer. There are brewery managers rejoicing in my survival.

That sip might have been the final straw for my body’s resistance after the reckless way that I treated bees. I never feared them; perhaps that’s why I got stung so often. All inadvertently – never wilfully. Maybe my allergy was caused by unintentionally stepping on a bee that was seeking spilled water around a swimming pool. It understandably stung me in its kamikaze defence, releasing pheromones that attracted its friends before I could dive into the pool.

You must understand that I have never treated them poorly or raided their hives. I have allowed them to crawl over me unhindered and saved them from drowning, yet I face death by bee.

My property near the Zambezi-Chobe confluence has at least four wild hives at any time, in an era when their numbers are dramatically declining worldwide. They represent as much danger to me as do the elephants, buffaloes, and lions that I encounter on my early morning walks with my dogs and the cobras, mambas and puffadders that share my domain.

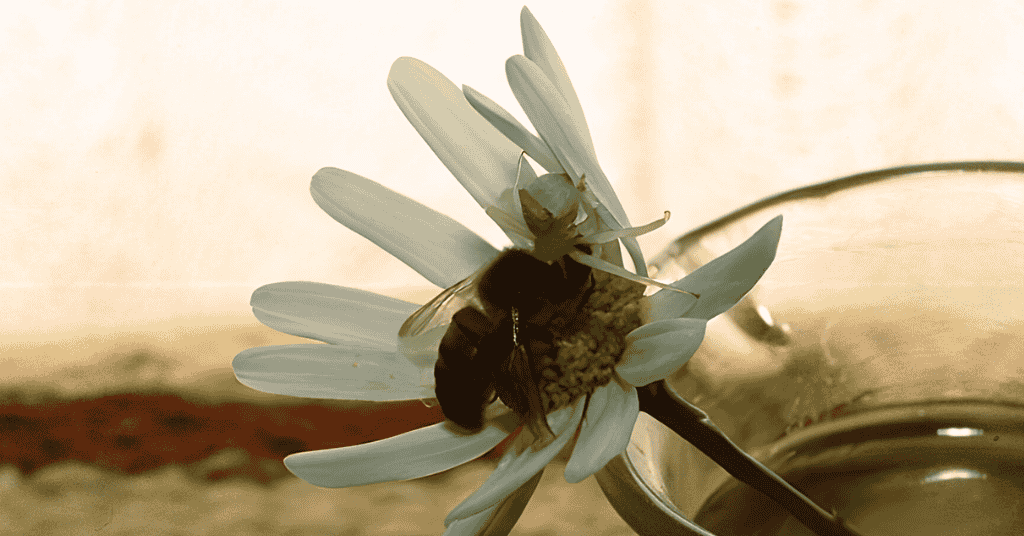

I admire bees for the wonderful product of evolution that they are. Together with flowers they share an intimate and ancient relationship, one built on mutual benefit and biological brilliance. Flowers, in their vibrant hues and alluring fragrances, or so we are told, have evolved a suite of characteristics to attract bees, who, in turn, play the crucial role of pollination. This beautiful dance of nature ensures the survival of flowering plants while providing bees with the sustenance they need to thrive.

At the heart of this partnership lies nectar, a sugary liquid produced by flowers as a reward for pollinators. For bees, nectar is a vital source of energy, fuelling their tireless flights and the activities of their hive. The floral scent of nectar, we are told, is especially enticing, drawing bees in from considerable distances. Once collected, this precious liquid is transformed into honey, the lifeblood of the hive during lean seasons.

While nectar satisfies the energy needs of bees, pollen offers them the proteins and nutrients essential for rearing their young. Bees, equipped with specialized hairy bodies, are adept at collecting pollen from the anthers of flowers, often transporting it back to their hives in noticeable yellow clumps on their hind legs. This protein-rich treasure feeds their larvae, ensuring the colony’s next generation thrives.

But what guides bees to flowers in the first place? It is a common belief that their exceptional colour vision plays a pivotal role. Bees are drawn to blue, violet, and yellow colours they perceive most vividly. Intriguingly, many flowers exhibit ultraviolet (UV) patterns invisible to human eyes. These UV markings act as natural roadmaps, leading bees straight to the nectar, a feature that underscores the evolutionary symbiosis between plants and pollinators.

Equally important to this attraction is the fragrance emitted by flowers. With their acute sense of smell, bees are quick to detect the volatile compounds that blooms release, essentially broadcasting their nectar reserves. Some plants have even fine-tuned their scent emissions to peak during the hours when bees are most active, ensuring they don’t miss out on their buzzing visitors.

The structure of flowers is another fascinating element in this relationship. Open or tubular shapes are particularly inviting, allowing bees easy access to their rewards. Petals often serve as sturdy landing platforms, while textures may provide grip during a bee’s meticulous foraging. Certain plants, especially those reliant on specific bee species, have evolved forms tailored to the anatomy of their preferred pollinators, further emphasizing the collaborative bond between them.

Beyond sight and scent, warmth and motion may also play a part in the allure of flowers. Some blooms offer slightly warmer centres, a welcome comfort for bees, particularly on chilly days. Swaying in the breeze, flowers mimic the movement of active plants, a subtle cue that helps bees distinguish them from their surroundings.

A new study dismisses these theories of attraction of bees to flowers and says that it all comes down electrical charges. The Earth is negatively charged, and as a species that grow in the earth, flowers are also negatively charged. Bees, while flapping their wings at an incredible 200 beats per second become positively charged and it is this duality of charges which attracts them to flowers. Once nestled on the flower their positive charges are dissipated which they recharge by taking the nectar back to the hive and by flying around in search of another flower.

Whichever theory is correct this intricate relationship between bees and flowers is a testament to the interconnectedness of life on Earth. Flowers depend on bees for pollination to ensure their reproduction, while bees rely on flowers for sustenance. Together, they not only sustain each other but also underpin ecosystems and agriculture worldwide. Their collaboration is one of nature’s most poetic partnerships, offering a reminder of the delicate balances that shape our world.

Bees have been on Earth for approximately 120 million years, dating back to the time when flowering plants began to proliferate. They are believed to have evolved from predatory wasps, transitioning to a diet of nectar and pollen. The earliest known bee fossil, Melittosphex burmensis, was discovered preserved in amber in Myanmar and is about 100 million years old. This ancient bee exhibited characteristics similar to both modern bees and their wasp ancestors, highlighting the evolutionary transition.

This co-evolution between bees and flowering plants played a critical role in shaping modern ecosystems, as bees became one of the primary pollinators for many plant species. Since their emergence, bees have extraordinarily diversified into over 20,000 species worldwide, adapting to a wide range of habitats and playing a vital role in sustaining ecosystems. These species include not only the honey bees (that produce roughly 1/12th of a teaspoon of honey in their lifetimes so please appreciate the sacrifice for your breakfast toast), bumble bees (which cope in colder climes), carpenter bees (which may bore holes in your woodwork but which are great pollinators), stingless bees ( harmless but irritatingly persistent as in mopane flies) and sweat bees who are attracted to human sweat.

Humans are threatening the survival of many of these bee species in real ways. Our widespread use of pesticides affects their nervous systems causing disorientation and reducing their foraging abilities. Our population expansion is creating habitat loss as we replace natural environments with vast concrete environments and monoculture farming. Cultivating bees and transporting them to monoculture farms, at huge cost to the farmer, is encouraging the spread of diseases and parasites with indeterminate results. It also has the potential of weakening colonies and spreading diseases that could escape into the greater bee world. Man-made changes in climate are disrupting the flowering times of plants and affecting the synchrony between bees and their food sources. There is no question that pollution of air, water and soil impacts bees negatively and one can only imagine what light pollution does to nocturnal bees who navigate by starlight.

All of us go through our day without giving a thought to bees. Why should we? We have so much to deal with in our own lives. None of us have the time to bother with every insect, fish, plant or even mammal that we hear is in distress. There are others who can deal with that.

Here is why I think that we should care about what we are doing to our environment. We are talking about bees but there is no living thing on Earth that does not influence everything else in the web of life.

If bees were to go extinct the consequences would be devastating for ecosystems, agriculture, and food security. Bees are critical pollinators for about 75% of the world’s major crops. Their extinction would drastically reduce the production of fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds, leading to major shortages and inevitable increased food prices putting many essential foods beyond the reach of most.

Bees play a vital role in maintaining healthy ecosystems by enabling plant reproduction. Numerous wild plants would struggle to reproduce, leading to ecosystem imbalances and biodiversity loss.

The decline of plant species would have cascading effects, disrupting food chains and leading to the collapse of ecosystems that depend on them. Many nutrient-rich foods, like almonds, apples, and blueberries, depend on bee pollination. A decline in these foods could lead to dietary imbalances and nutritional deficiencies worldwide. Livestock feed, such as alfalfa and clover, also relies on pollination. A decrease in these crops would affect livestock farming, further straining food systems. Bees support the survival of many species by maintaining plant diversity. Their extinction would trigger a domino effect, endangering numerous other species dependent on plants and the ecosystems bees help sustain.

The bottom line is that we really need bees.

If we globally adopt a political policy of drill, drill, drill for oil for the benefit of a handful of billionaires we are all just one figurative bee sting from death.

The consequences of electing people whose egos don’t allow them to exhibit common sense or appreciate the value of all life in its varied forms will not result in the end of the world—she will survive for billions of years, until the death throes of the sun swallow our lonely planet—but in the untimely extinction of many of its miraculous life forms, including ours.