You have made good progress in keeping to your selected direction, but so far, you have not come across any signs of human activity. The sun is dipping towards the horizon, so it is easier to keep to a southerly path. You hasten your pace, glancing ever more frequently to your right at the sun that is dipping alarmingly quickly. You really don’t want to spend a night alone in the bush. You remember all too vividly the hyena calls that thrilled you last night from the safety of your tent. Without that tent, the thrill would turn to terror.

You are so focused on haste and direction that you don’t notice the young bull elephant not far away until you are uncomfortably close. His ears are spread wide, his trunk curled—its tip sniffing the air—and he is shuffling backwards and forwards, uncertainly. You are left in no doubt that he is agitated. His forefoot scuffs the ground, and then he starts to trundle forward. At first, it’s deliberate, but like a train gathering momentum, his speed increases. He is closing the distance at an alarming rate. There are few things more intimidating than having three tons of the most powerful animal on earth bearing down on you. Should you stand still and wait for it to trample you, maybe throw you over its shoulder before kneeling on you and driving a tusk through your chest? You realise that you only have seconds to decide. You glance around. There is no sizeable tree to dodge behind. You look back. The massive beast is almost on top of you. Your fight-or-flight instinct kicks in. You obviously can’t fight something that impossibly enormous, so you run.

The last thing that you feel… ever… is a ridiculously powerful thump to your back.

Your last thought is, “What should I have done?”

For those of us who have been in a similar situation and survived, I doubt that there is one who did not consider fleeing as a first option. The first time that I was charged by a huge bull elephant, I fled, but only because I needed to take three hurried steps to reach the safety of a canvas wall where I was out of sight. The other occasions were not so comfortable. It takes resolve to face down a bulky, agitated creature, but the thing is that if you stand your ground and calmly wave your arms—or better, a stick or a hat—your chances of survival are significantly increased. I urge you to look on YouTube to see how my good friend Al McSmith handled himself when confronted by a feisty bull. His client, who calmly filmed the incident, displayed immense trust in his guide. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J9WW3QbOgQA

Now let us suppose that it was a lion and not an elephant that charged you—an animal that might have more interest in eating you than trampling you. What is your best chance of not becoming lunch? Lions generally hunt by forcing their prey to bolt, and they use their sheer speed and power to leap on their shoulders. I promise you that you will not outrun a lion in a footrace. As with a charging elephant, it does take resolve to stand your ground when the king of the jungle is coming straight at you with intent. I speak from experience when I tell you this—I have been charged by a pride of lionesses who were protecting their cubs, and I have been hunted when on foot at night. If I had not stood my ground, I would not be writing this now. Wave your arms. Appear unafraid, even threatening, no matter how you feel inside. If you have something at hand to throw, then throw it. I don’t care if it is your brand-new AI Swarovski binoculars that you mortgaged your spouse for, or your state-of-the-art camera with its weighty lens. Throw it with all your force and scream your frustration at the expense as you do so. Lions did not evolve to hunt anything that behaves like that. They will back off. But don’t assume it’s over, though, because they might not go far. Back off slowly, keeping an eye on them. Pick up a stick or stone if you can, so you have something to throw at them if they charge again.

Should you fear cheetahs and wild dogs? The good news, among all this angst, is that neither cheetahs nor wild dogs present a threat to humans. We just aren’t on their evolutionary menu, which is just as well in the case of wild dogs, as they are the most efficient hunters. As they are too small to kill us outright, they would eat us alive by taking bites out of us until we died from shock, blood loss, or damage to a vital organ. Thank heaven that they are fussy eaters and almost disdainfully ignore us, although one time when I was sitting on the ground watching them, a couple of curious dogs came right up to me and sniffed me just as their unrelated domestic counterparts might do.

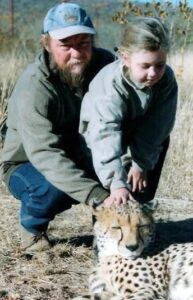

I have felt firsthand just how terrifying it is to have the fastest animal on land charge you. A cheetah’s speed defies belief. I was with my young daughter at a cheetah rescue in Namibia, and we were inside the fenced area where the cats were kept when Skye noticed a young Damara dik-dik—a tiny antelope—standing next to the fence. She wanted to go up to it, and the little thing stood there as we approached and started to suckle at a finger that I poked through the fence. I became aware of a movement behind me and looked back to see a cheetah in full flight heading straight for us. For the split second that I had time to think, I was petrified that Skye was the target, but it was the dik-dik. The cat was only metres away from us, sprinting at full speed—which is well over a hundred kilometres per hour—when it saw the fence. I learned then that cheetahs can stop even faster than they can accelerate. It stopped within a metre of realising that it was about to hit the fence. My heart, I believe, also stopped.