You have calmed the rising panic that you felt when you realised that you were abandoned in the wilderness, and you have considered your options. If you follow the group that left you behind, you will be heading into unfamiliar country, you reason. If you lose their tracks, there is nothing around you that you will be able to recognise to help find your way back to the trail. Of course, it may be much shorter that way, but there is no way of telling. Maybe someone in the group will realise that you are missing, and they might turn back to look for you. But if you have lost their tracks and you don’t meet up with them, you are in trouble, so you decide to double back the way you came. You guess that you must have walked for about five hours before the lunch break, and if you can maintain a similar speed, you should make it back to camp before dark.

You easily find where the group walked into the small picnic area because the sand was soft, and the tracks are easy to see. You were straggling behind before lunch, and your boot tracks are on top of the others. They are clear, deep prints, and that may help you.

As you set off, it probably won’t occur to you that you are quite possibly invoking the oldest science known to man. According to Louis Liebenberg, a man with an interesting mind, who wrote a book titled The Art of Tracking: The Origin of Science, tracking is the source of our sciences. Man developed his ability to track prey out of absolute necessity. He had to teach himself to track to stay alive—rather like the situation that you now find yourself in. Frankly, I can’t think of any science that could possibly predate this one or was more instrumental in the survival and evolution of our species unless it was using plants for food and medicinal purposes.

You focus your attention on following the tracks. While the path is sandy, the tracks are easy to follow, and you maintain a good pace. But then the trail leads you across a large plain of long grass. You remember this because the grass is so tall in places that you have limited visibility, and you were worried about walking into an elephant or a buffalo. Beyond the plain lies harder ground. Here you start to realise that you have to pay very close attention. When you hit a rocky area, you despair—the tracks disappear altogether. You lose the tracks, and panic rises again.

What should you do in this situation? When you are tracking people—especially a large group like you were with—they will always leave signs, however subtle, that can be picked up. The first thing to remember is that there is a rhythm, a cadence, to walking in the bush. The leader will subconsciously or by design select a general direction to travel—in this case, he may have selected a large circle or possibly more of a square, as it is easier to follow one direction than a gentle turn, so that he can arrive back at camp, which was your starting point. Within that general direction is the natural tendency to use the path of least resistance, so he will make use of existing game trails and select open ground as opposed to heading through thick bush. In addition, people tend to favour one side or another—often their dominant side—when going around an obstacle like a tree or bush. You remember that your guide is right-handed, so you may want to look carefully on the left-hand side of any obstacle as your first option. Open country also offers visibility with a lower risk of being surprised by an aggressive animal, so if there is a stand of impenetrable bush, then expect that you would have walked around it.

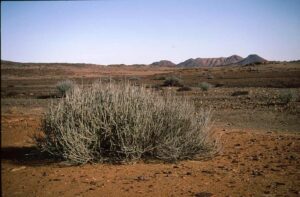

Sandy and wet ground leave deep prints where it is easy to follow tracks. If you walked through long grass, it will have been pushed over in the direction that you were going, which is also easy to follow. Where the ground is hard and dry, it can get tricky. You should be looking for tell-tale scuffs where a boot has scraped on the ground. An overturned leaf will be darker on its underside, and a disturbed pebble will often leave a small pockmark from the build-up of sand around it caused by rain or wind. The pebble itself, if it was overturned, will often look encrusted with sand on the underside. Broken twigs are sometimes indications of your group passing, and keep an eye out for signs of someone stopping for a pee or spitting out a grass stalk that they were chewing on. You are looking for small signs. On rocky areas where few signs are left behind, look for leaves and pebbles, but most importantly, try to read the terrain and predict the likeliest path taken. Look around you for signs of things that may have registered on your earlier walk—a hill, an unusual tree, a gully. If you don’t see anything that jogs your memory, go to the farthest end of the rocky area and carefully check the edge of the rock for likely paths, scuff signs—anything that will give you an indication of recent human activity. A carelessly discarded sweet wrapper could become a lifesaver.

You have tried anything that you can think of, and you can’t find any sign of the group having passed this way. Your tracking time is over, you reluctantly concede. You feel vulnerable and alone, and you have used up valuable time. You need to try something else to get to camp before dark. You really don’t want to spend a lonely night out in the bush with the prospect of hyenas, lions, and leopards on the prowl.

What is your next move? Think about what you would do, and we will discuss my suggestions in an upcoming blog.